Interesting digital humanities data sources

I bookmark sources of data that seem interesting for digital humanities teaching and research:

- showing humanists what data & datafication in their fields can look like

- having interesting examples when teaching data-using tools

- trying out new data tools

I’m focusing on sharing bookmarks with data that’s already in spreadsheet or similar structured format, rather than e.g.

- collections of digitized paper media also counting as data and worth exploring, like Josh Begley’s racebox.org, which links to full PDFs of US Census surveys re:race and ethnicity over the years; or

- 3D data, like my colleague Will Rourk’s on historic architecture and artifacts, including a local Rosenwald School and at-risk former dwellings of enslaved people

Don’t forget to cite datasets you use (e.g. build on, are influenced by, etc.)!

And if you’re looking for community, the Journal of Open Humanities Data is celebrating its 10th anniversary with a free, global virtual event on 9/26 including “lightning talks, thematic dialogues, and community discussions on the future of open humanities data”.

Data is being destroyed

U.S. fascists have destroyed or put barriers around a significant amount of public data in just the last 8 months. Check out Laura Guertin’s “Data, Interrupted” quilt blog post, then the free DIY Web Archiving zine by me, Quinn Dombrowski, Tessa Walsh, Anna Kijas, and Ilya Kreymer for a novice-friendly guide to helping preserve the pieces of the Web you care about (and why you should do it rather than assuming someone else will). The Data Rescue project is a collaborative project meant “to serve as a clearinghouse for data rescue-related efforts and data access points for public US governmental data that are currently at risk. We want to know what is happening in the community so that we can coordinate focus. Efforts include: data gathering, data curation and cleaning, data cataloging, and providing sustained access and distribution of data assets.”

Interesting datasets

The Database of African American and Predominantly White American Literature Anthologies

By Amy Earhart

“Created to test how we categorize identities represented in generalist literature anthologies in a database and to analyze the canon of both areas of literary study. The dataset creation informs the monograph Digital Literary Redlining: African American Anthologies, Digital Humanities, and the Canon (Earhart 2025). It is a highly curated small data project that includes 267 individual anthology volumes, 107 editions, 319 editors, 2,844 unique individual authors, and 22,392 individual entries, and allows the user to track the shifting inclusion and exclusion of authors over more than a hundred-year period. Focusing on author inclusion, the data includes gender and race designations of authors and editors.”

National UFO Reporting Center: “Tier 1” sighting reports

Via Ronda Grizzle, who uses this dataset when teaching Scholars’ Lab graduate Praxis Fellows how to shape research questions matching available data, and how to understand datasets as subjective and choice-based. I know UFOs sounds like a funny topic, and it can be, but there are also lots of interesting inroads like the language people use reflecting hopes, fears, imagination, otherness, certainty. A good teaching dataset given there aren’t overly many fields per report, and those include mappable, timeline-able, narrative text, and a very subjective interesting one (a taxonomy of UFO shapes). nuforc.org/subndx/?id=highlights

The Pudding

Well researched, contextualized, beautifully designed data storytelling on fun or meaningful questions, with an emphasis on cultural data and how to tell stories with data (including personally motivated ones, something that I think is both inspiring for students and great to have examples of how to do critically). pudding.cool

…and its Ham4Corpus use

Shirley Wu for The Pudding’s interactive visualization of every line in Hamilton uses my ham4corpus dataset (and data from other sources), which might be a useful example of how an afternoon’s work with open-access data (Wikipedia, lyrics) and some simple scripted data cleaning and formatting can produce foundations for research and visualization.

Responsible Datasets in Context

Dirs. Sylvia Fernandez, Miriam Posner, Anna Preus, Amardeep Singh, & Melanie Walsh

“Understanding the social and historical context of data is essential for all responsible data work. We host datasets that are paired with rich documentation, data essays, and teaching resources, all of which draw on context and humanities perspectives and methods. We provide models for responsible data curation, documentation, story-telling, and analysis.” 4 rich dataset options (as of August 2025) each including a data essay, ability to explore the data on the site, programming and discussion exercises for investigating and understanding the data. Datasets: US National park visit data, gender violence at the border, early 20th-century ~1k poems from African American periodicals, top 500 “greatest” novels according to OCLC records on novels most held by libraries. responsible-datasets-in-context.com

Post45 Data Collective

Eds Melanie Walsh, Alexander Manshel, J.D. Porter

“A peer-reviewed, open-access repository for literary and cultural data from 1945 to the present”, offering 11 datasets (as of August 2025) useful in investigations such as how book popularity & literary canons get manufactured. Includes datasets on “The Canon of Asian American Literature”, “International Bestsellers”, “Time Horizons of Futuristic Fiction”, and “The Index of Major Literary Prizes in the US”. The project ‘provides an open-access home for humanities data, peer reviews data so scholars can gain institutional recognition, and DOIs so this work can be cited’: data.post45.org/our-data.html

CBP and ICE databases

Via Miriam Posner: A spreadsheet containing all publicly available information about CBP and ICE databases, from the American Immigration Council americanimmigrationcouncil.org/content-understanding-immigration-enforcement-databases

Data assignment in The Critical Fan Toolkit

By Cara Marta Messina

Messina’s project (which prioritizes ethical critical studies of fan works and fandom) includes this model teaching assignment on gathering and analyzing fandom data, and understanding the politics of what is represented by this data. Includes links to 2 data sources, as well as Destination Toast’s “How do I find/gather data about the ships in my fandom on AO3?”.

(Re:fan studies, note that there is/was an Archive of Our Own dataset—but it was created in a manner seen as invasive and unethical by AO3 writers and readers. Good to read about and discuss with students, but I do not recommend using it as a data source for those reasons.)

Fashion Calendar data

By Fashion Institute of Technology

Fashion Calendar was “an independent, weekly periodical that served as the official scheduling clearinghouse for the American fashion industry” 1941 to 2014; 1972-2008’s Fashion International and 1947-1951’s Home Furnishings are also included in the dataset. Allows manipulation on the site (including graping and mapping) as well as download as JSON. fashioncalendar.fitnyc.edu/page/data

Black Studies Dataverse

With datasets by Kenton Ramsby et al.

Found via Kaylen Dwyer. “The Black Studies Dataverse contains various quantitative and qualitative datasets related to the study of African American life and history that can be used in Digital Humanities research and teaching. Black studies is a systematic way of studying black people in the world – such as their history, culture, sociology, and religion. Users can access the information to perform analyses of various subjects ranging from literature, black migration patterns, and rap music. In addition, these .csv datasets can also be transformed into interactive infographics that tell stories about various topics in Black Studies. “ dataverse.tdl.org/dataverse/uta-blackstudies

Netflix Movies & Shows

kaggle.com/datasets/shivamb/netflix-shows

Billboard Hot 100 Number Ones Database

By Chris Dalla Riva

Via Alex Selby-Boothroyd: Gsheet by Chris Dalla Riva with 100+ data fields for every US Billboard Hot 100 Number One song since August 4th, 1958.

Internet Broadway Database

Found via Heather Froehlich: “provides data, publishes charts and structured tables of weekly attendance and ticket revenue, additionally available for individual shows”. ibdb.com

Structured Wikipedia Dataset

Wikimedia released this dataset sourced from their “Snapshot API which delivers bulk database dumps, aka snapshots, of Wikimedia projects—in this case, Wikipedia in English and French languages”. “Contains all articles of the English and French language editions of Wikipedia, pre-parsed and outputted as structured JSON files using a consistent schema compressed as zip” huggingface.co/datasets/wikimedia/structured-wikipedia. Do note there has been controversy in the past around Hugging Face scraping material for AI/dataset use without author permission, and differing understandings of how work published in various ways on the web is owned. (I might have a less passive description of this if I went and reminded myself what happened, but I’m not going to do that right now.)

CORGIS: The Collection of Really Great, Interesting, Situated Datasets project

By Austin Cory Bart, Dennis Kafura, Clifford A. Shaffer, Javier Tibau, Luke Gusukuma, Eli Tilevich

Visualizer and exportable datasets of a lot of interesting datasets on all kinds of topics.

FiveThirtyEight’s data

I’m not a fan for various reasons, but their data underlying various political, sports, and other stats-related articles might still be useful: [data.fivethirtyeight.com(https://data.fivethirtyeight.com/) Or look at how and what they collect, include in their data and what subjective choices and biases those reveal :)

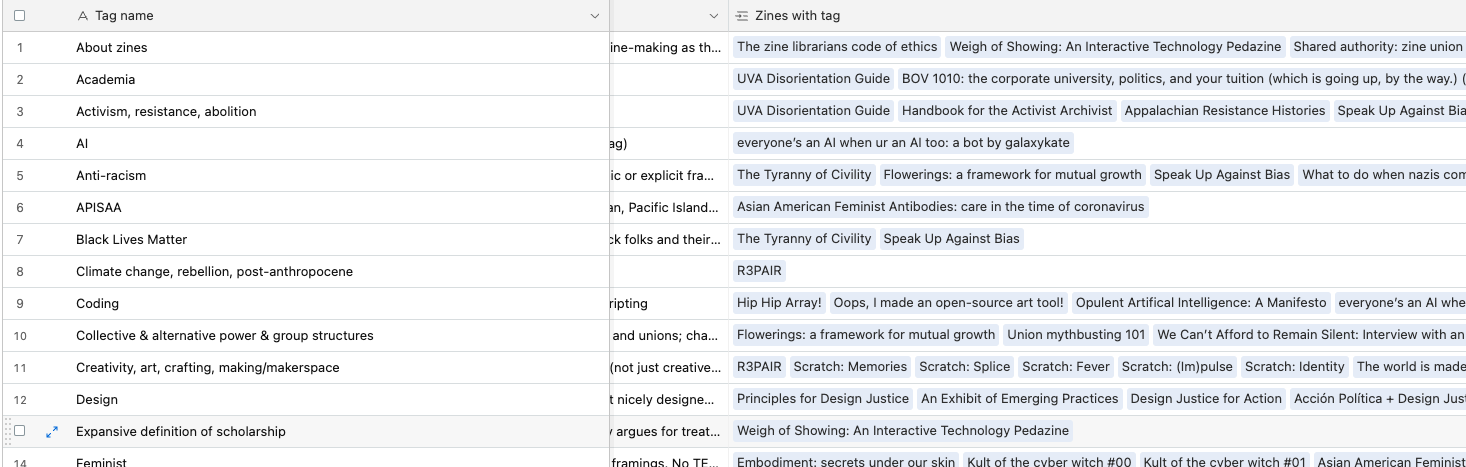

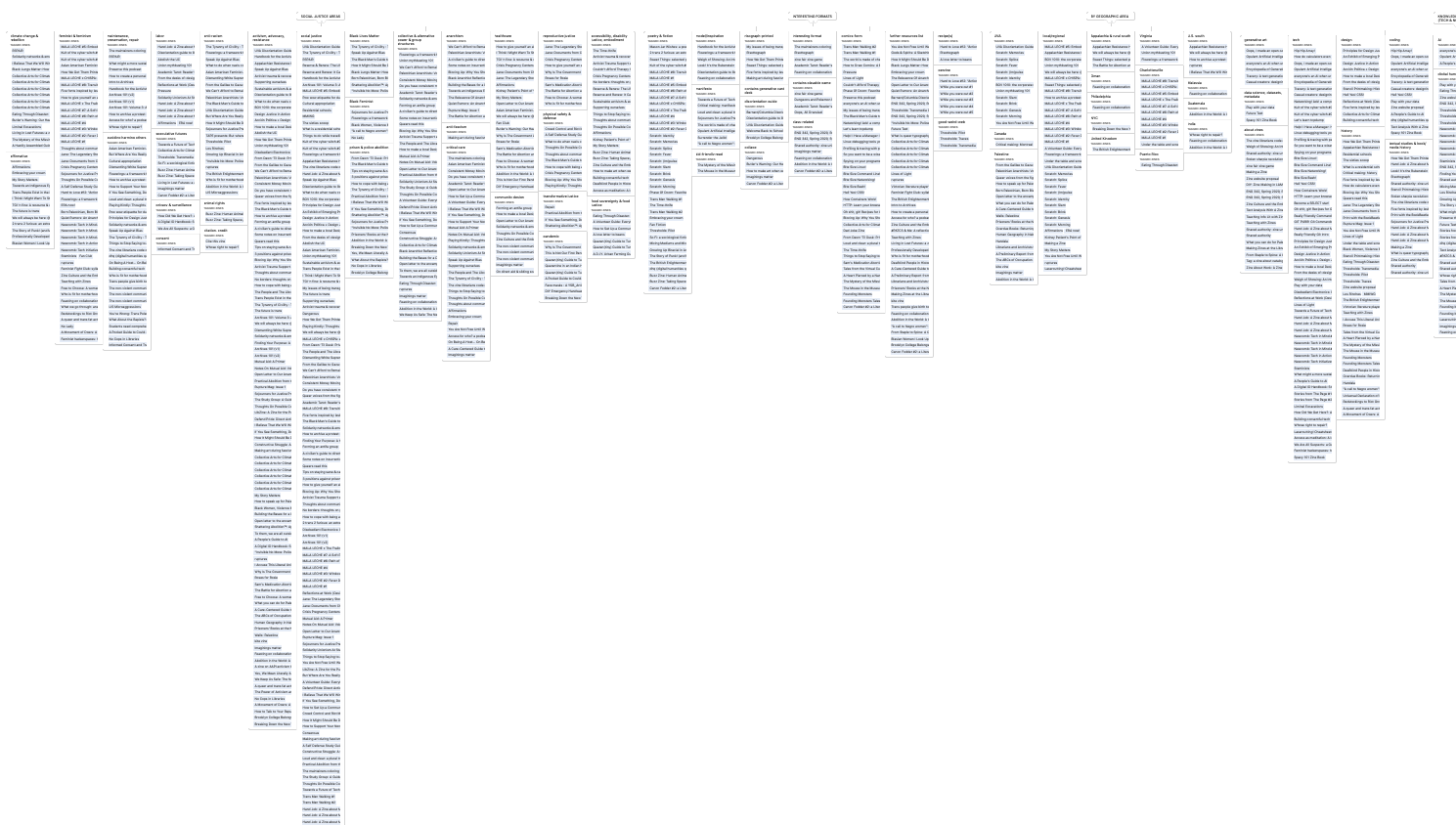

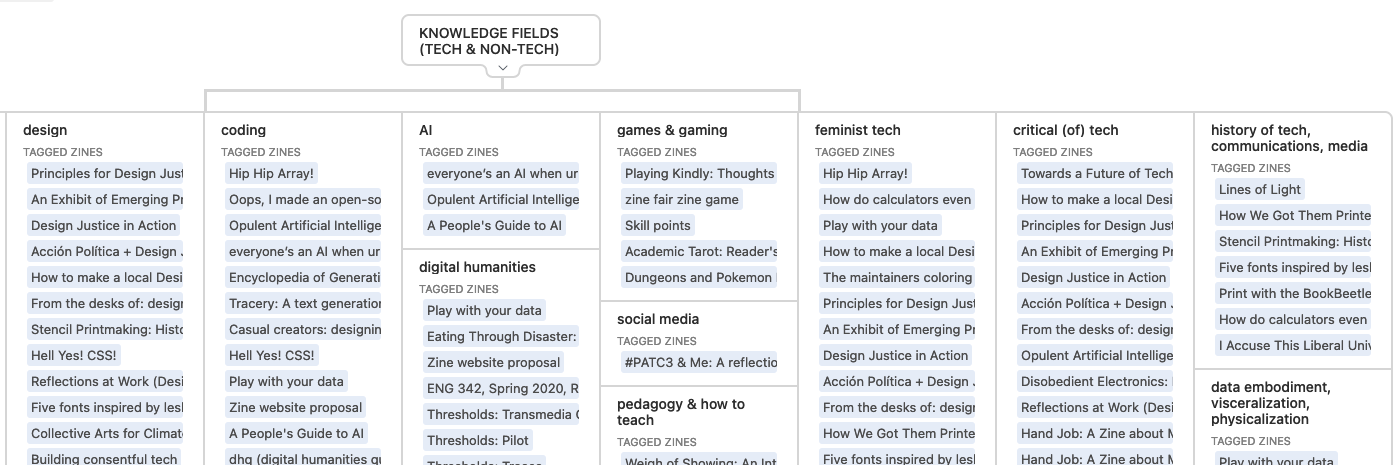

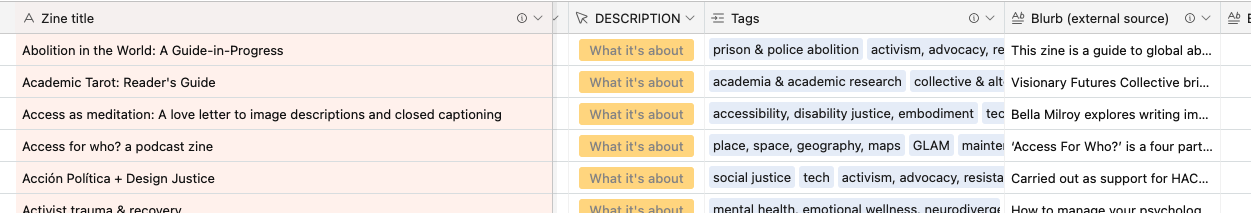

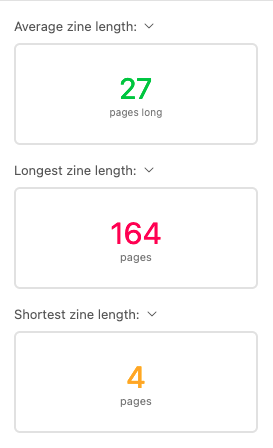

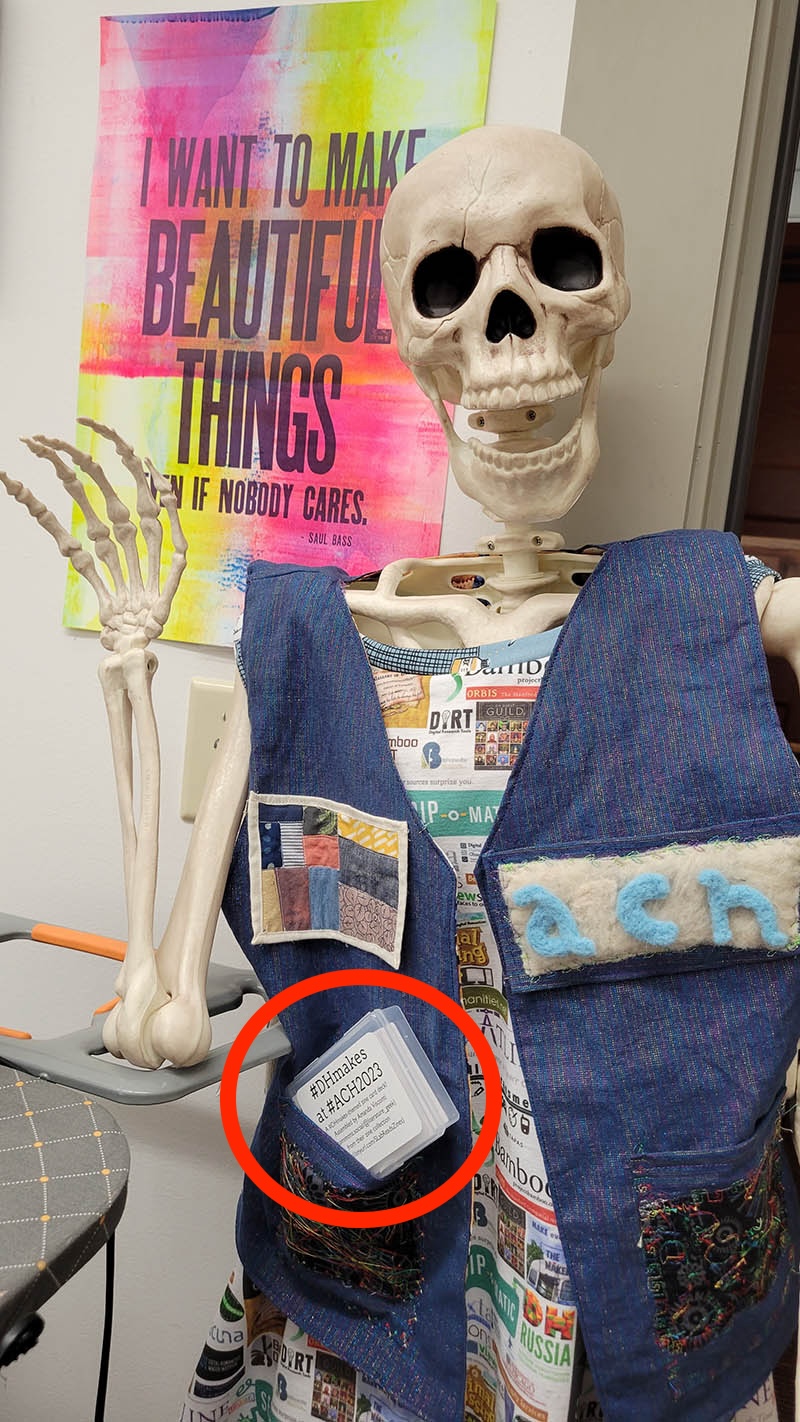

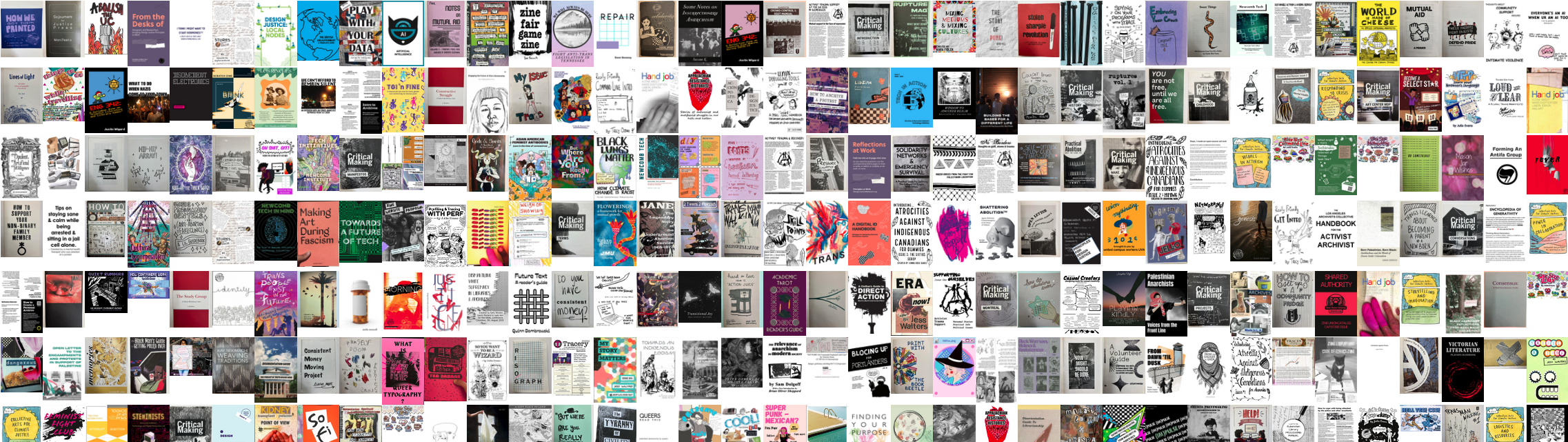

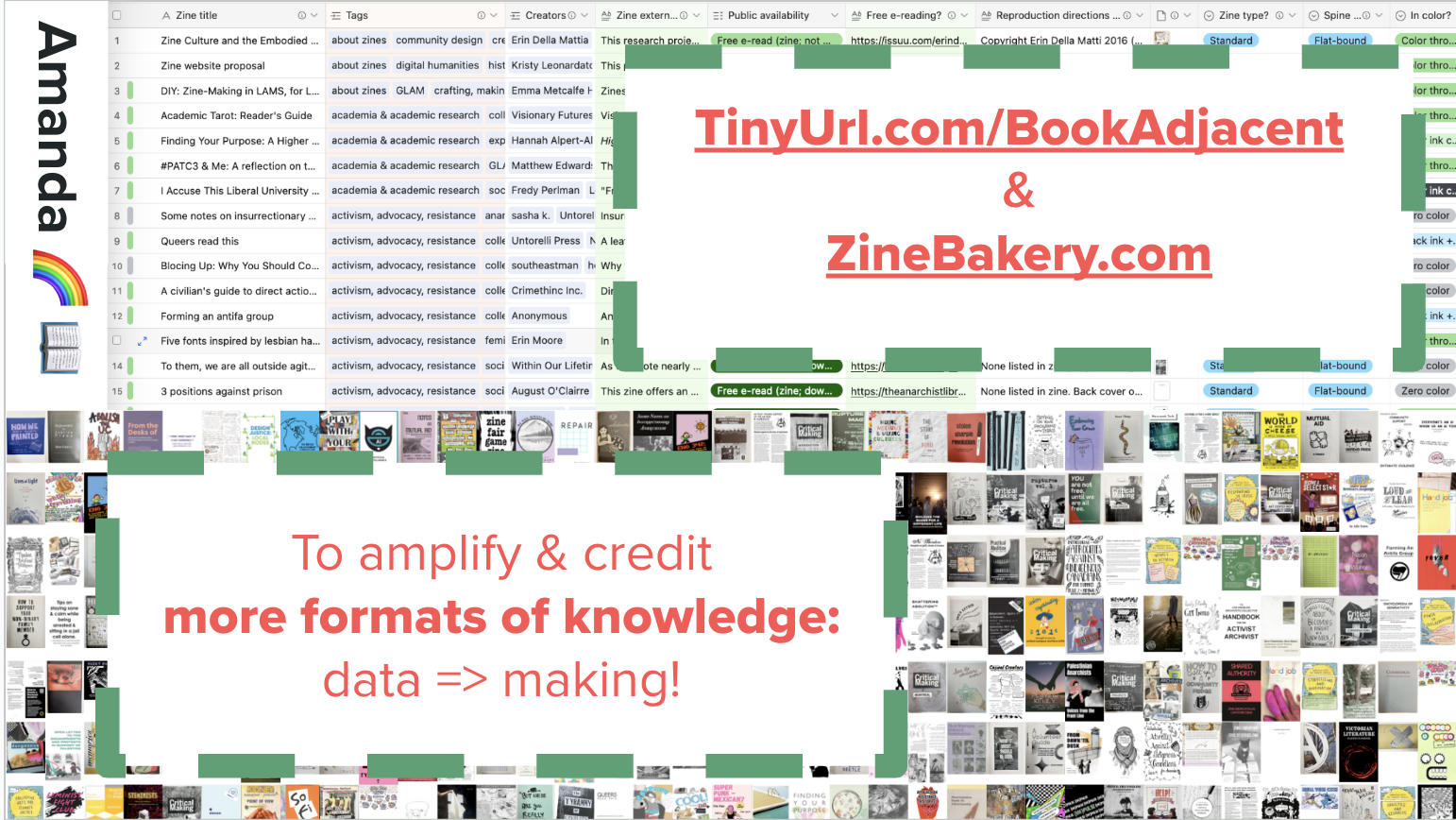

Zine Bakery zines

I maintain a database of info on hundreds of zines related to social justice, culture, and/or tech topics for my ZineBakery.com project—with over 60 metadata fields (slightly fewer for the public view) capturing descriptive and evaluative details about each zine. Use the … icon then “export as CSV” to use the dataset (I haven’t tried this yet, so let me know if you encounter issues).

OpenAlex

I don’t know much about this yet, but it looked cool and is from a non-profit that builds tools to help with the journal racket (Unsub for understanding “big deals” values and alternatvies, Unpaywall for OA article finding). “We index over 250M scholarly works from 250k sources, with extra coverage of humanities, non-English languages, and the Global South. We link these works to 90M disambiguated authors and 100k institutions, as well as enriching them with topic information, SDGs, citation counts, and much more. Export all your search results for free. For more flexibility use our API or even download the whole dataset. It’s all CC0-licensed so you can share and reuse it as you like!” openalex.org

Bonus data tools, tutorials

Matt Lincoln’s salty: “When teaching students how to clean data, it helps to have data that isn’t too clean already. salty offers functions for “salting” clean data with problems often found in datasets in the wild, such as pseudo-OCR errors, inconsistent capitalization and spelling, invalid dates, unpredictable punctuation in numeric fields, missing values or empty strings”.

The Data-Sitters Club for smart, accessible, fun tutorials and essays on computational text analysis for digital humanities.

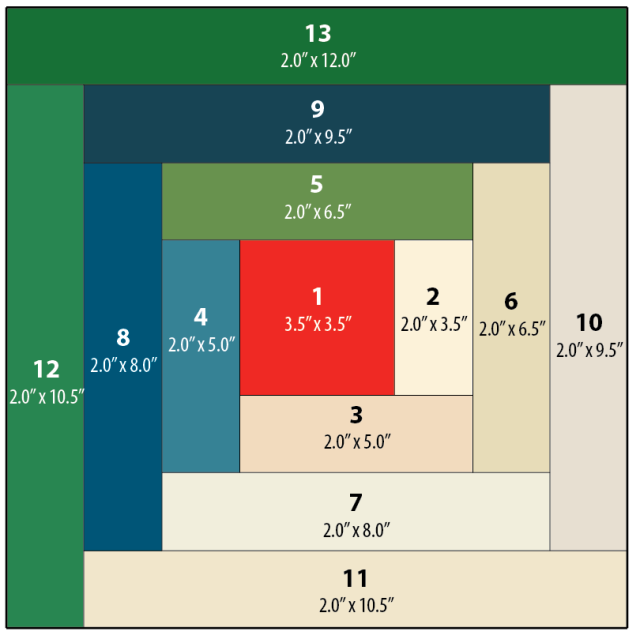

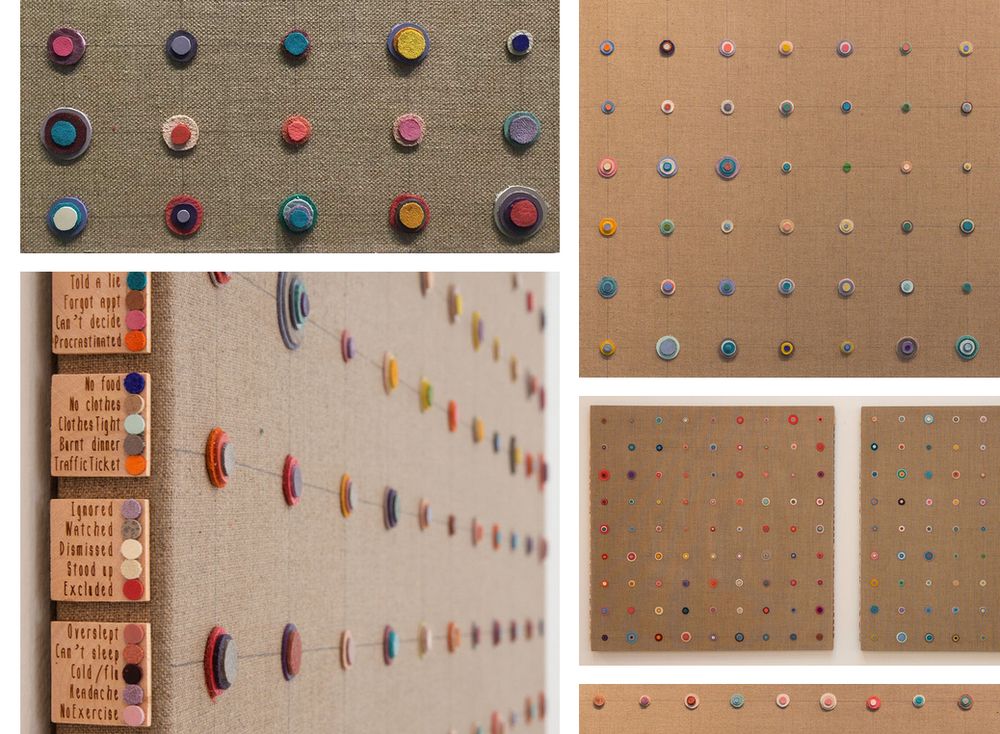

Claudia Berger’s blog post on designing a data physicalization—a data quilt!—as well as the final quilt and free research zine exploring the data, its physicalization process, and its provocations.

The Pudding’s resources for learning & doing data journalism and research

See also The Critical Fan Toolkit by Cara Marta Messina (discussed in datasets section above), which offers both tools and links to interesting datasets.

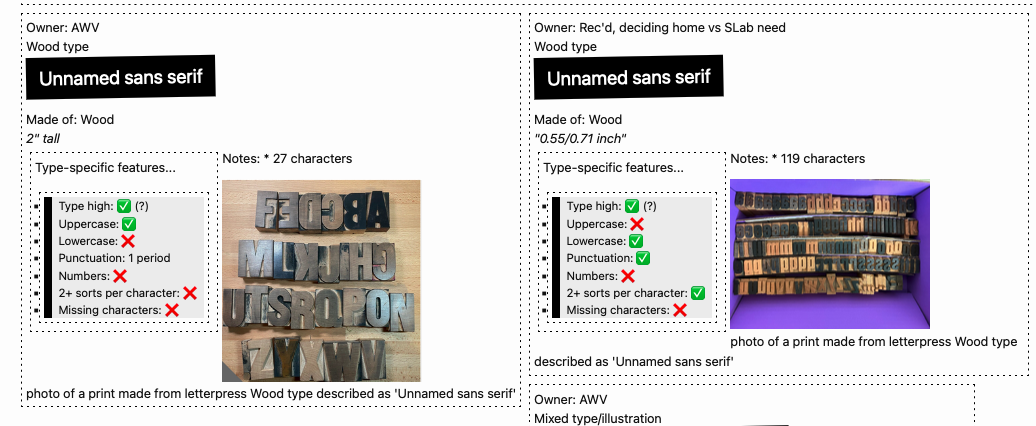

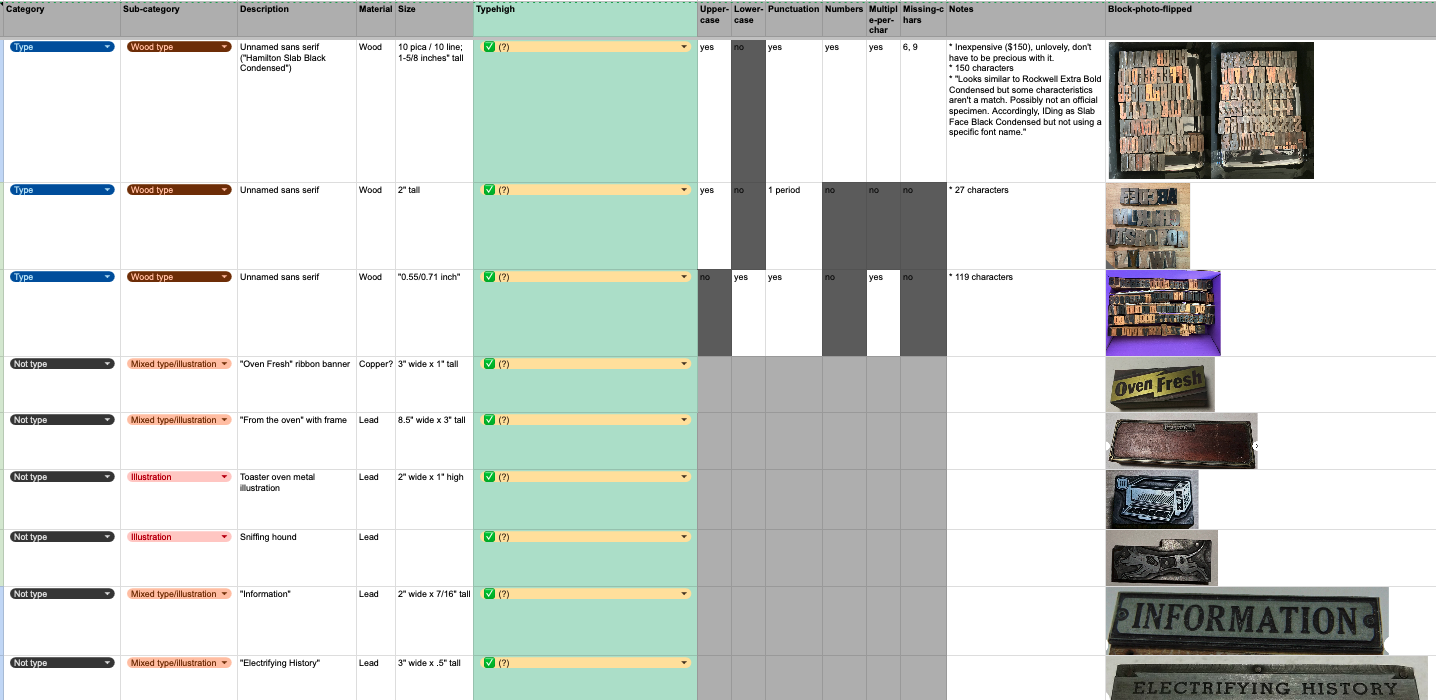

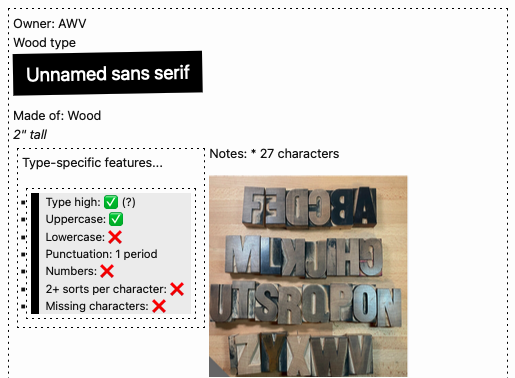

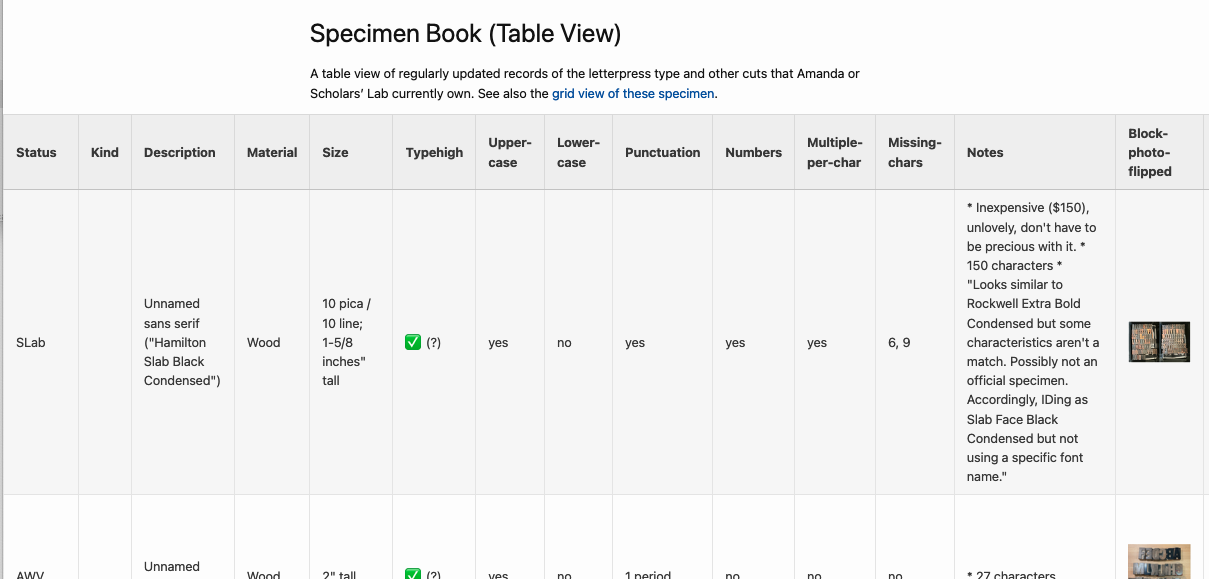

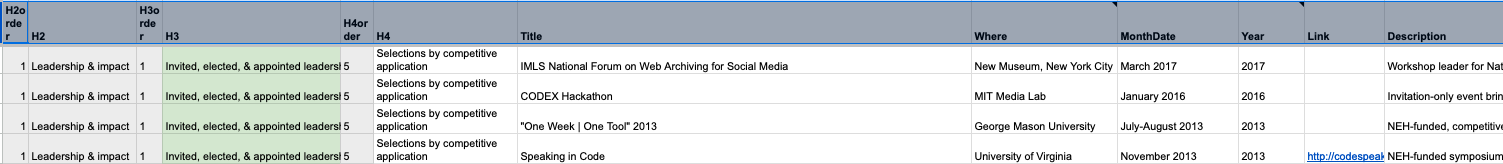

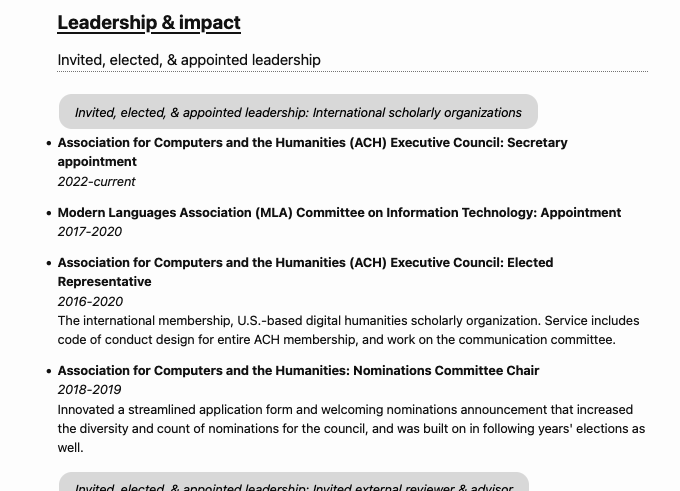

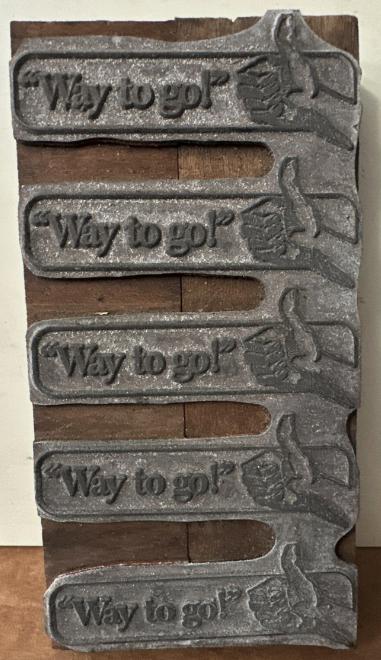

Letterpress data, not publicly available yet…

I maintain a database of the letterpress type, graphic blocks/cuts, presses, supplies, and books related to book arts owned by me or by Scholars’ Lab. I have a very-in-progress website version I’m slowly building, without easily downloadable data, just a table view of some of the fields.

I also have a slice of this viewable online and not as downloadable data: just a gallery of the queerer letterpress graphic blocks I’ve collected or created. But I could get more online if anyone was interested in teaching or otherwise working with it?

I also am nearly done developing a database of the former VA Center for the Book: Book Arts Program’s enormous collection of type, which includes top-down photos of each case of type. I’m hoping to add more photos of example prints that use each type, too. If this is of interest to your teaching or research, let me know, as external interest might motivate me to get to the point of publishing sooner.

These are not the final colors that I will be using. They will probably all be changed once I dye the fabric and know what I am working with.

These are not the final colors that I will be using. They will probably all be changed once I dye the fabric and know what I am working with.

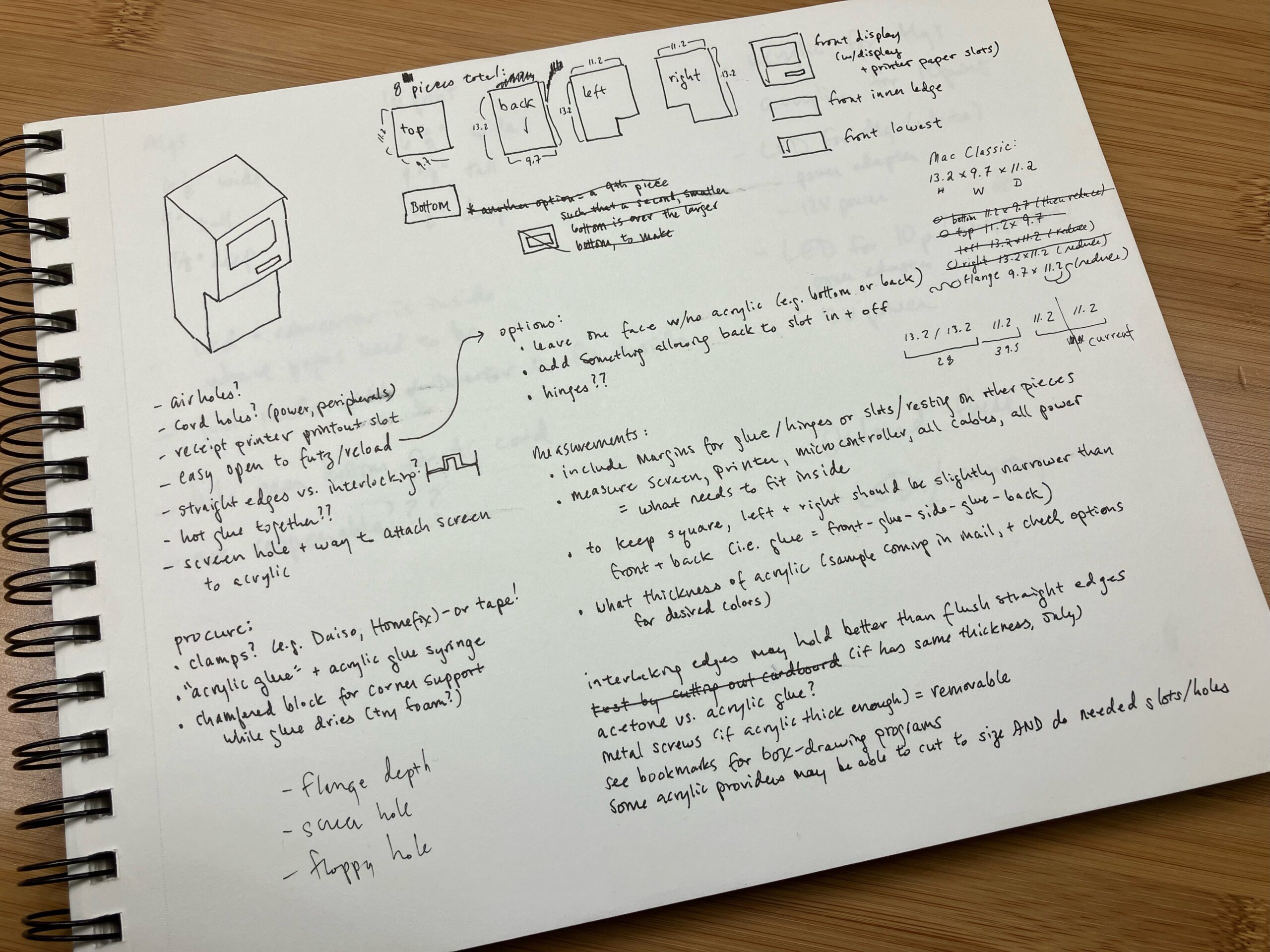

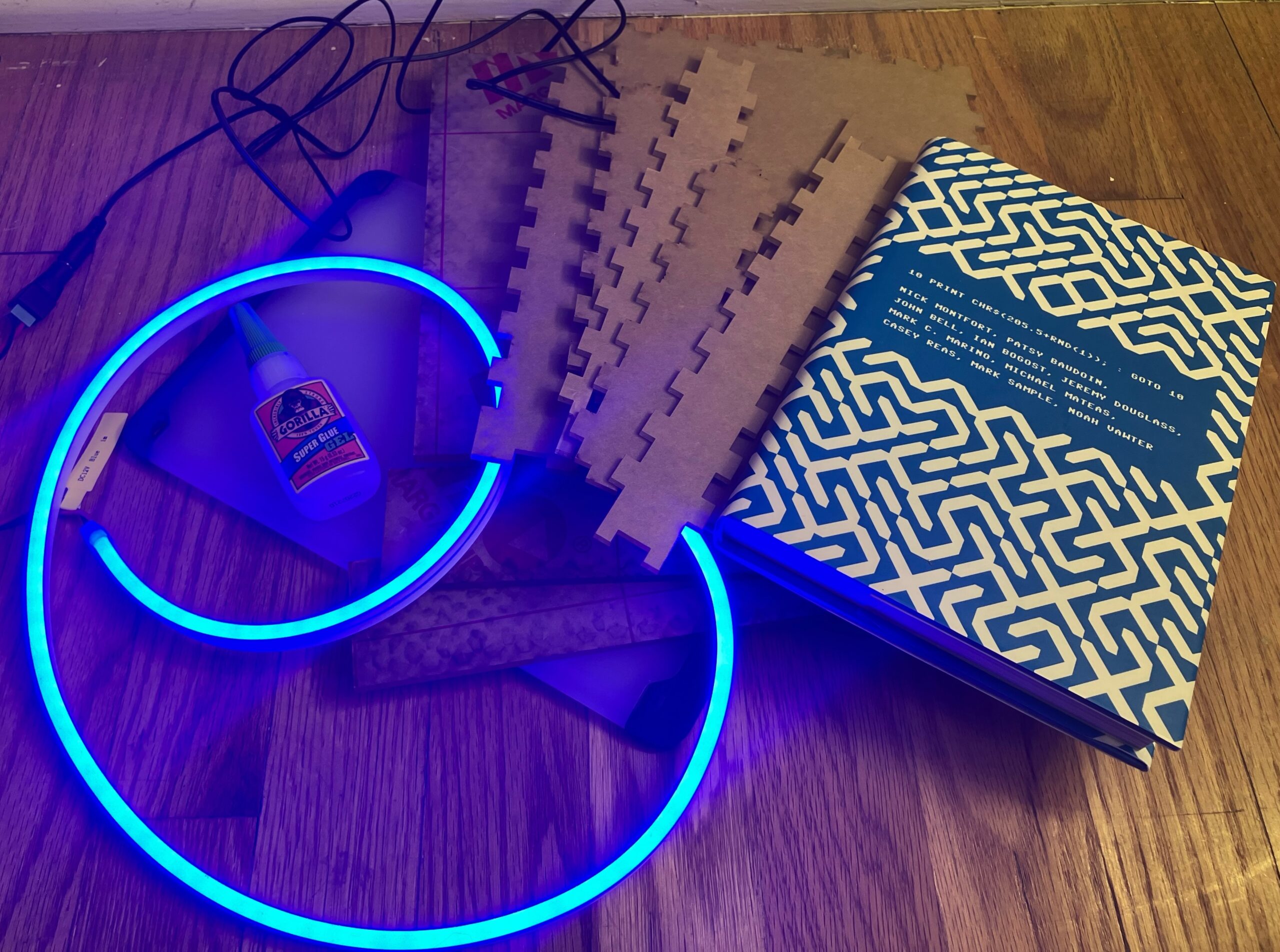

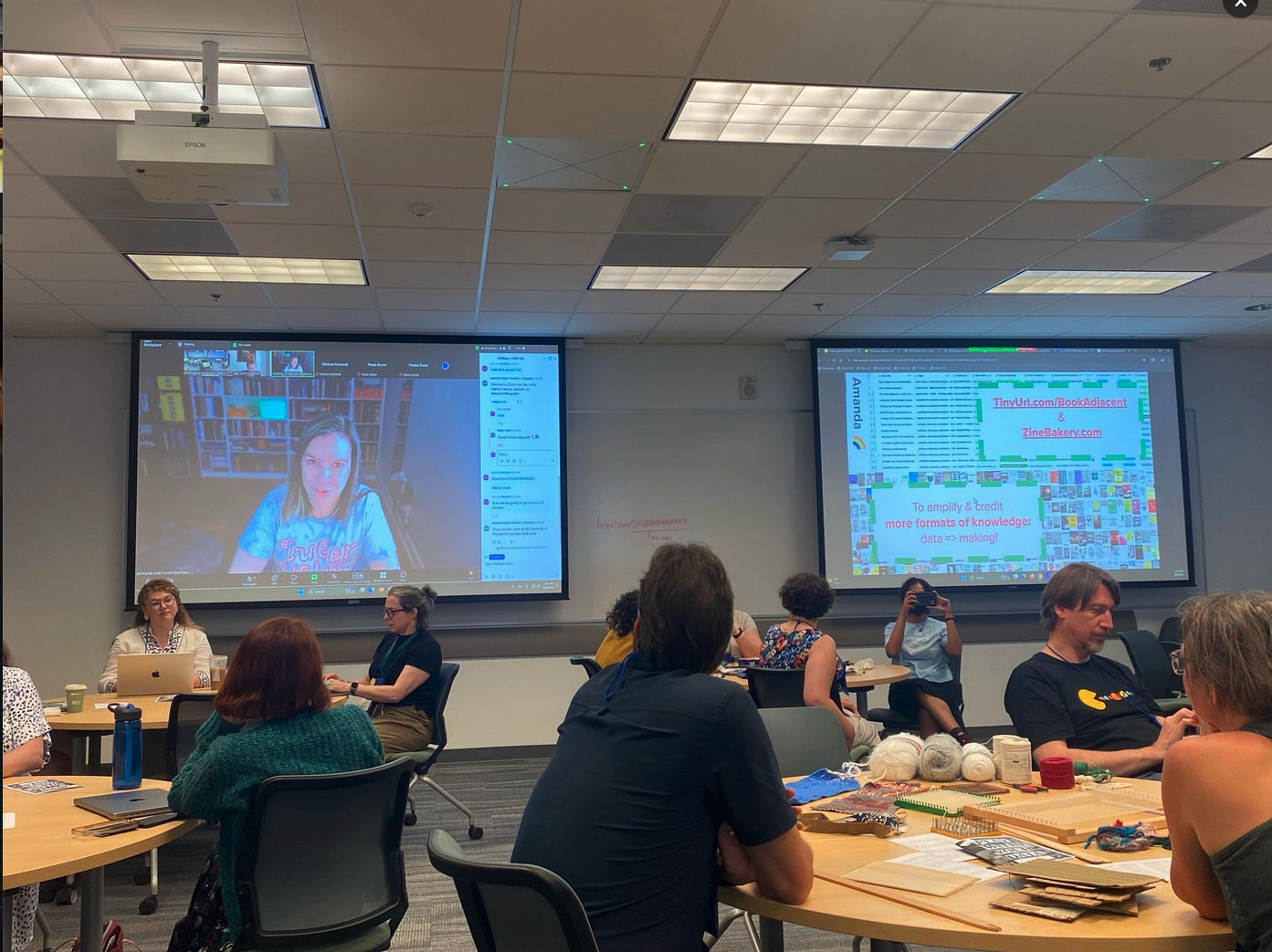

Giving a talk on data-driven making for the DH 2024 conference

Giving a talk on data-driven making for the DH 2024 conference