阅读视图

Omeka S

Omeka S

Tool Description: Omeka S is a web publishing platform for digital artifacts. Think about an Omeka project as a big collection of items, and the sites are individually curated exhibits.

Guides & Tutorials

The Quick Guides and Interactive Tutorials on this page have been created by the Digital Scholarship team at the University Libraries to help you learn the ins and outs of Omeka S.

Quick Guides to Omeka S

Resources

The Alabama Digital Humanities Center hosts and supports basic Omeka S projects for faculty on campus for the purpose of research and teaching. See these resources for other hosting solutions and additional support!

The post Omeka S appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

Writing as Muscle

Rebecca Foote recently invited me to a part of an ACH panel on publishing in digital humanities along with Jojo Karlin and Nat McGartland. You can find other posts related to that conversation here.

During the recent ACH panel on DH publishing, Jojo Karlin commented on the sheer quantity of public writing that the Scholars’ Lab puts out into the world. In the moment, I flippantly referred to that volume as a kind of sickness that we couldn’t turn off. But I followed up with a more serious answer: as I mentioned in a previous post, I’ve been making a concerted effort to write every day lately as a response to the cataclysmic political times that we live in. The real truth is that I believe it would become much harder for me to write if I were to slow down. Sharing things publicly is really an accountability mechanism more than anything else, a way to force myself to keep writing.

There’s an old saying among music teachers that practicing for one hour daily is more useful than practicing for seven hours once a week. There are a few thoughts behind this. For one, you actually damage your muscles beyond a productive state if you work yourself to the point of exhaustion. By contrast, the same amount of time measured out equally across a week yields a consistent and healthy amount of stress on your muscles, recovery time, and rest to build up the neural pathways in your brain that you ultimately want to get from practicing. The once weekly seven-hour approach is also less likely to yield useful practice time. With a big stretch of time like that you will, at best, need breaks. At worst, you will find yourself distracted, pick up your cell phone, or your brain will wander. It’s difficult to imagine what you would practice for seven hours in a row, let alone the degree of concentration that would be required to sustain it. You’ll be better at deliberate, intentional practice every day.

I’ve been approaching writing the same way. I’ll share a follow-up post about some different tools and tactics I use to keep the pace, but the underlying idea behind all this is that writing is a muscle, a skill that you can practice. If you do it every day, writing ultimately becomes easier whenever you sit down to do it. The approach is akin to what Twyla Tharp calls “the creative habit,” and I have had to get creative to keep it going. Somedays I will have a substantial chunk of time, but those days are rare luxuries. It’s more common for me to be scrambling to find a way to fit writing in however I can. Even five minutes at the desk matters—it’s a way to shake off the rust. I only have ten minutes while walking? I can spend it dictating into my phone. Two minutes before a meeting waiting for others to arrive? I can make some quick notes.

Therein lies the real secret: the daily approach is a way to save time in the long run. I learn how to write regardless of whether inspiration is striking. Since starting this practice, my voice is much easier to find when sitting down to write. The editorial process feels easier to navigate; I’m much less given to endless tinkering. I need writing to be as natural and easy as possible, and the daily practice is essential for that. Sitting down to a blank page is always frightening. It would be immeasurably scarier if I weren’t facing it down everyday.

In short, I don’t write every day because I have oceans of time. I write every day because I don’t have time to waste, and the muscle needs to stay loose to confront that reality.

Couch to Paragraph Writing Program

If you’ve ever hung out with me for more than a few seconds, you know that I’m obsessed with process. I’m always talking about some new thing that I’m trying. I’ll do X thing over Y number of days until I reach some milestone goal. Cleaning, reading, listening to music—they’ve all been the subject of some program I’m trying out. Obviously not all of these schemes stick. My latest goal has been to blog every week, though, and I’ve been doing a pretty good job so far this semester of keeping up with it. This impulse to write consistently is my own way to try and deal with the political climate we’re living in. After all, if writing didn’t matter, the powers that be wouldn’t try so strongly to silence disagreeing voices. Jeff Tweedy’s How to Write One Song has a great quote to that effect that has really stuck with me: “We have a choice— to be on the side of creation, or surrender to the powers that destroy.” I’ve been trying to cultivate this practice of creation for myself. My long-term goal is to make progress on my book project, something that often gets kicked to the back burner. To make this happen, I’ve decided to spend some time each day writing in whatever capacity I can.

At the same time, I’ve also been trying to get back into exercise, something I have never been fairly attentive to. When I was a kid, I was the least athletic person possible. As an adult I’m a bit better but only just. I’ll run for a bit, push too hard, then stop for a while. I’ve been trying something different lately. Rather than running until I hurt myself, as I usually do when I try to get back into it, I’m working through a couch to 5k program. I’m honoring the real needs of my body, starting basically from nothing and building up to a healthier lifestyle.1

In this context, I’ve been thinking about writing like a muscle. How can I exercise my creative skills such that, when I sit down to write, I’m not waiting for inspiration to strike? What would it mean to build daily writing up in a sustainable practice? What would a writing plan that asks you to create every day look like if it was modeled on a running program?

I set about putting together a writing plan with this framing in mind. In running, conventional wisdom is that you only want to be adding distance or increasing speed any given week—not both. Applying this to writing, I aimed to produce a concrete number of words each day as opposed to, say, writing for a specified amount of time. This meant that I could fit my work into the cracks between things, typing on my phone or dictating while driving. I developed a plan for myself modeled on running programs that start out with small, set intervals—e.g., run for 15 seconds, walk for two minutes, run for 30 seconds, walk for two minutes. The proportions change, and the amount increases week by week.

Without further ado, here is the plan that I wrote and executed for myself in April:

- Week 1:

- Write one book sentence every workday.

- Write one sentence of creative work each day on the weekend.

- Week 2:

- Write two book sentences every workday.

- Write two sentences of creative work each day on the weekend.

- Week 3:

- Write three book sentences every workday.

- Write three sentences of creative work each day on the weekend.

- Week 4:

- Write four book sentences every workday.

- Write four sentences of creative work each day on the weekend.

My goals were very modest starting out: just craft one sentence. Each day, I added pebble by pebble to my final product, a mound that grew over the course of the month. This might feel ridiculous. What is the point of writing one sentence? How can you even get into that mindset? Fair critiques. It depends on how you work, but this is also part of the point. I treated it like an exercise by warming up. For me, this most often meant that I would spend five minutes while driving just thinking and then ten minutes dictating. At first, I intentionally stopped myself after the target number of sentences, but I would make a note of the upcoming topic for the next day’s work. Hemingway famously suggested that you stop writing in the middle of a sentence, and I similarly tried to make sure that the next day’s work would be ready to go. The pivot to creative work on the weekends was a way to keep my momentum going while adopting a restful mentality, a way to tie in something enjoyable while still respecting work/life boundaries. The creative work has been incredibly nourishing, and the practice has really helped push my writing muscles.

I’ve been very satisfied with the results of this program, and I’m going to keep it going as long as I can. Writing aside, I found that I was in a much better mood each day this past month knowing that I was creeping along. By the end of the month, I was writing nearly a full paragraph each day, and I abandoned my goal to stop writing after reaching my target. I found that I kept finding new ways to fit words in—five minutes here, five minutes there. Huge chunks of time are a luxury; I need to be able to grab the words when I can. All those sentences will accumulate. Slow progress still goes forward.

Gotta start walking.

-

Just to keep myself honest, I feel compelled to say that I have let the exercise lapse again. I’ve got a child who just learned how to run, and I’ve been spending my time chasing after him. The writing continues though! ↩

The M.E. Test

I recently gave a workshop for the US Latino Digital Humanities Center (USLDH) at the University of Houston on introductory text analysis concepts and Voyant. I don’t have a full talk to share since it was a workshop, but I still thought I would share some of the things that worked especially well about the session. USLDH recorded the talk and made it available here, and you can find the link to my materials here.

I had a teaching observation when I was graduate student, and one comment always stuck with me. My director told me, “this was all great but don’t be afraid to tell them what you think.” I’ve written elsewhere about how I tend to approach classroom facilitation as a process of generating questions that the group explores together. This orientation is sometimes in conflict with DH instruction, where you have information that simply needs to be conveyed. I had this tension in mind while planning the USLDH event. It was billed as a workshop, and I think there’s nothing worse than attending a workshop only to find that it’s really a lecture. How to balance the generic expectations with the knowledge that I had stuff I needed to put on the table? As an attempt to thread this needle, I structured the three-part session around a range of different kinds of teaching moves: some lecture, yes, but also a mix of open discussion, case study, quiz questions, and free play with a tool.

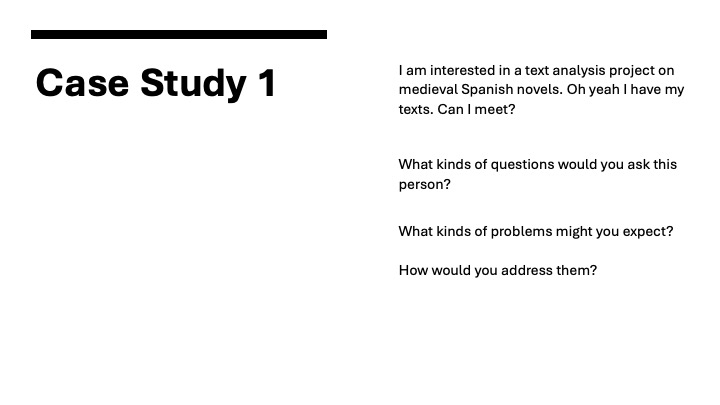

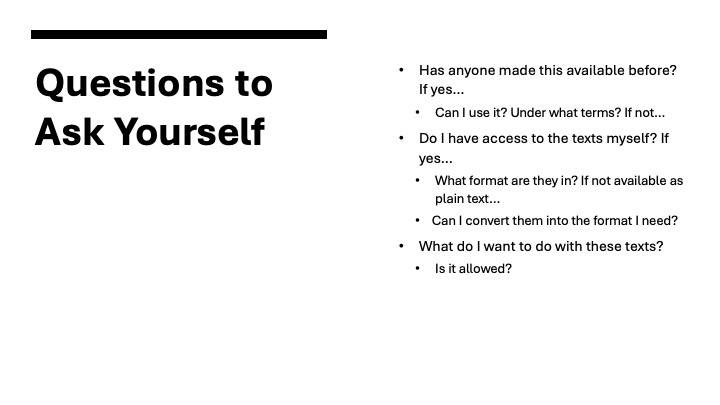

The broad idea behind the workshop entitled “Book Number Graph” is that people come to text analysis consultations with all varieties of materials and a range of research questions. Most often, my first step in consulting with them is to ask them to slow down and think more deeply about their base assumptions. Do they actually have their materials in a usable form? Is it possible to ask the questions they are interested in using the evidence they have? I built the workshop discussions as though I was prepping participants to field these kinds of research consultations, as though they were digital humanities librarians.

First, the “book” portion of the workshop featured a short introduction to different kinds of materials, exploring how format matters in the context of digital text analysis. We discussed how a book is distinct from an eBook is distinct from a web material, and how all of these are really distinct from the kind of plain text document that we likely want to get to. I used here a hypothetical person who shows up in my office and says, “Oh yeah, I have my texts. I’m ready to work on them with you. Can you help me?” And they will hand me either a stack of books or a series of PDF files that haven’t been OCR’d. I introduced workshop participants to the kinds of technical and legal challenges that arise in such situations so that they’ll be able to better assess the feasibility of their own plans. This all built to a pair of case studies where I asked the participants how they would respond if a researcher came to them with questions for their own project.

With these case studies, I hoped to give participants a glimpse into the real-world kinds of conversations that I have as a DH library worker. For the most part, consultations begin with my asking a range of questions of the researcher so as to help them get new clarity on the actual feasibility of what they want to do. I hoped for the participants to question the formats of the materials for these hypothetical researchers and point out a range of ethical and legal concerns. Hopefully they would be able to ask these questions of their own work as well.

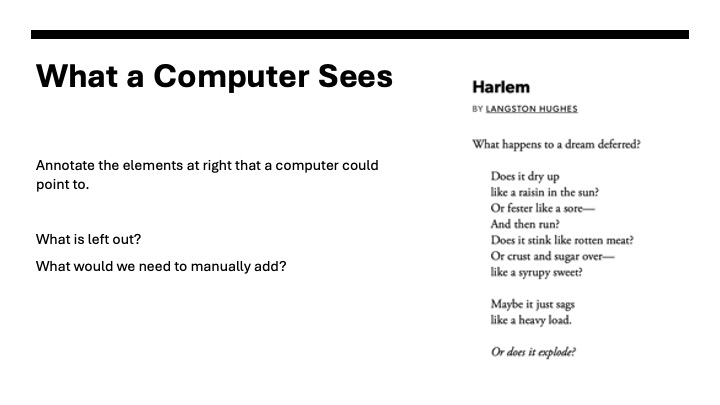

For the second section of the workshop entitled “number,” I gave participants an introduction to thinking about evidence and analysis, distinguishing between what computers can do and the kinds of things that readers are good at. Broadly speaking, computers are concrete. They know what’s on the page and not what’s outside of it. Researchers in text analysis need to point software to the specific things that they are interested in on the page and supplement this information with any other information outside of the text. Complicated text analysis research questions have at their core really simplistic, concrete, measurable things on the page. You are pointing to a thing and counting. For examples of the things that computers can readily be told to examine, we discussed structural information, proximity, the order of words, frequency of words, case, and more.

To practice this, I adapted an exercise that I was first introduced to by Mackenzie Brooks but that was developed by librarians at the University of Michigan. To introduce TEI, the activity asks students to draw boxes around a printed poem as a way to identify the different structural elements that you would want to encode. For my purposes, I put a Langston Hughes poem on the Zoom screen and asked participants to annotate it with all sorts of information that they thought a computer would be capable of identifying.

The result was a beautiful tapestry of underlines and squiggles. Some of the choices would be very easy for a computer: word frequency, line breaks, structural elements. But we also talked about more challenging cases. We know the poem’s title because we expect to see it in a certain place on the page. The computer might be pointed to this this by flagging the line that comes three after three blank line breaks. But what if this isn’t always the case? It was good practice in how to distinguish between the information we bring to the text and what is actually available on the page. We talked about the challenges in trying to bridge the gap between what computers can do and what humans can do, to try and think through how a complicated intellectual question might take shape in a computationally legible form.

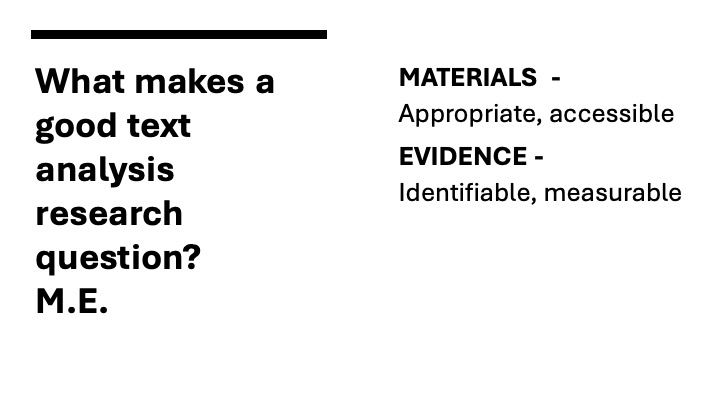

Wrapping all this together, I introduced what I called the M.E. test for text analysis research. To have a successful text analysis project you have to have…

- Materials that are…

- appropriate to your questions and

- accessible for your purposes.

You must also have

- Evidence that is…

- identifiable to you as an expression of your research question and

- legible to the tool you are using.

Materials and Evidence. M and E.

M.E.

The next time you sit down to do text analysis, ask yourself, “What makes a good question? M.E. Me!”

Painfully earnest? Sure! But this was a nice little way for me to tie in what I often joke is my most frequently requested consultation topic: imposter syndrome. The M.E. question is both a test for deciding whether or not a text analysis research question is appropriate, but it is also a call for you to recognize that you can handle this work. A nice little way for you to give yourself a pump up, because I believe that these methods belong to anyone. Anyone can handle these kinds of consultations. They’re more art than science at the level we are discussing. You just have to know the correct way to approach them. Deep expertise can come later. If you are too intimidated to get started you will never get there.

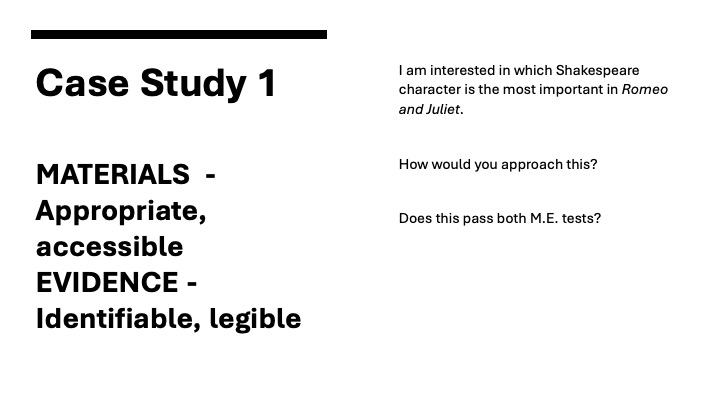

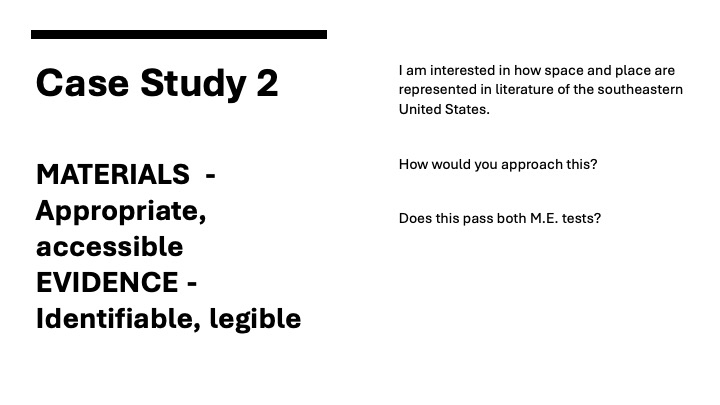

From there, I closed the “number” portion of the workshop with a couple more case study prompts. I asked participants to respond to two more scenarios as though someone had just walked into their office with an idea they wanted to try out.

The hypothetical consultation prompts involved, first, an interest in finding the most important characters in a particular Shakespeare play and, second, an interest in space and place in southeastern American literature. In each case, we discussed questions of format and copyright, but we also got to some fairly high-level questions about what kinds of evidence you could use to discuss the research questions. For importance, participants proposed measuring either number of lines for each character or who happens to be onstage for the greatest amount of time. For space and place, we discussed counting place names using Python (a nice way to introduce concepts related to Named Entity Recognition). In each case, my goal was to give the workshop participants a sense of how to test and develop their own research questions by walking them through the process I use when talking with researchers asking for a fresh consultation.

USLDH has shared the recording link, so feel free to check out the recording if you want to see the activities in action. The slides can be found here. And never forget the most important thing to ask yourself the next time you’re working on a text analysis problem:

“What makes a good research question? Me.”

Storymap Guide 06: Selecting a Map and Changing Your Map Marker

Learning Objectives: change the background map using a different map from the StorymapJS map library; upload a new custom map marker.

The post Storymap Guide 06: Selecting a Map and Changing Your Map Marker appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

Storymap Guide 05: Custom Text Formatting

Learning Objectives: apply html tags to text to create headings; numbered lists, and unnumbered lists; and paragraph breaks.

The post Storymap Guide 05: Custom Text Formatting appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

Storymap Guide 04: Share Your Storymap

Learning Objectives: share map with a public URL; share map as an embed on a website; share map by exporting as a file.

The post Storymap Guide 04: Share Your Storymap appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

Storymap Guide 03: Adding Location Slides

Learning Objectives: Create a new Storymap Slide; add a location to a Storymap Slide using an address; add a location to a Storymap Slide using a GIS reference.

The post Storymap Guide 03: Adding Location Slides appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

Storymap Guide 02: Adding Content to a Slide

Learning Objectives: create a slide headline; add and format descriptive text; embed media using an image address.

The post Storymap Guide 02: Adding Content to a Slide appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

Storymap Guide 01: Start a Project

Learning Objectives: Navigate storymap.knightlab.com; sign in with your Google account; and create a new project.

The post Storymap Guide 01: Start a Project appeared first on Alabama Digital Humanities Center.

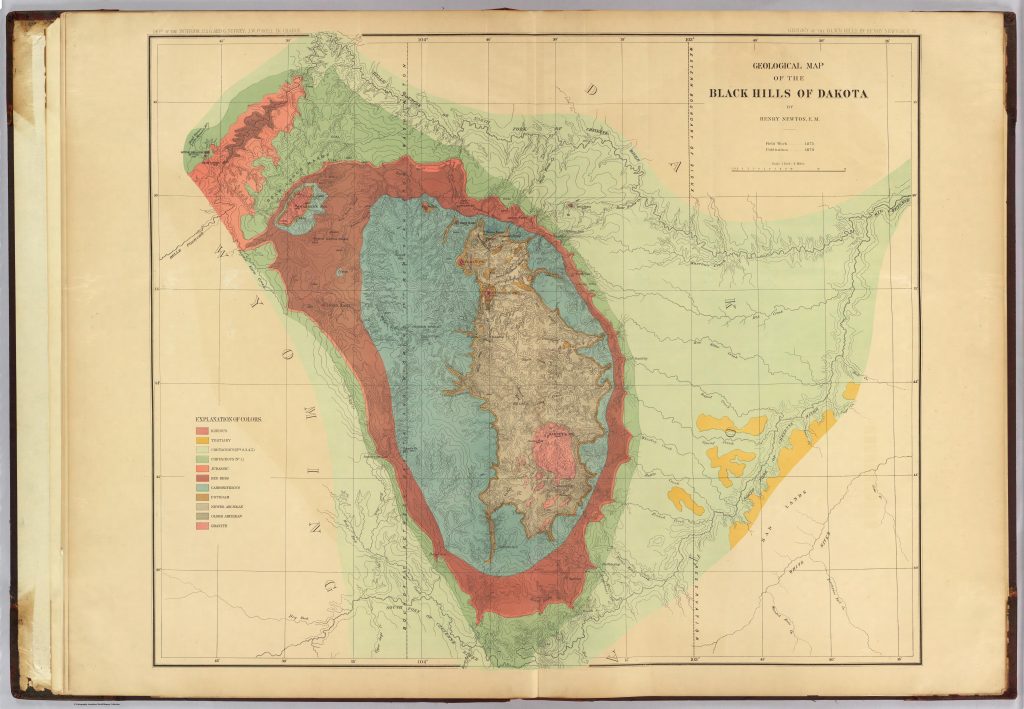

In and Out of Place: Resource Extractions from Treaty Lands

In and Out of Place: Resource Extractions from Treaty Lands

In and Out of Place: Resource Extractions from Treaty Lands uses a decolonizing, collaborative and Lakotan-centered approach to map scientific and military expeditions that entered the 1868 Treaty Territory in the Black Hills region from the mid-19th century to the turn of the 20th century. The project is a prototype map tracking Custer’s and other expeditions’ day-by-day travels across Treaty lands, contextualized with newspaper reports, journal entries, and other primary sources. “In and Out of Place” aims to generate interest and conversation among Lakotan and other Indigenous communities impacted by this history.

The project hopes to receive feedback from communities to guide its future directions and offer a space to think critically about the role of maps and other “objective” modes of scientific representation in the long history of American imperialism and settler colonialism.

Contributors: Craig Howe (co‑PI, CAIRNS); Lukas Rieppel (co‑PI); Tarika Sankar (CDS Lead); Khanh Vo (Digital Methods Lead); Audrey Wijono, Owen Blair, Cormac Collins, Dante Cavaz, Sofia Gonzalez, and Colten Edelman

The Rand Lab Data Archive

The Rand Lab Data Archive

More coming soon!

Research at Brown

Research at Brown

More coming soon!

NIH-funded SFHERE Project

NIH-funded SFHERE Project

More coming soon!

Omeka S

Omeka S