Stuffed animals, creativity, and other thoughts

When I was a kid, I spent hours playing with stuffed animals in a society I had created for them called AnimalLand. I remember designing and building homes using cardboard for the walls, which I then decorated with acrylic paint and wrapping paper (as wallpaper). I cobbled together a set of indoor furniture, complete with old dollhouse pieces and the three-legged miniature “tables” that were occasionally placed in the center of a pizza. I immersed myself fully in this world, creating and building on storylines that detailed the everyday lives of the stuffed animals. They lived in different towns (each named after rooms of the house, such as Kitchen Town), had friends and families, attended concerts and baseball games, and read The AnimalLand Gazette daily. Many of these stories are memorialized in old photos, home videos, and art projects that my brother and I created.

You may be familiar with stories such as The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams, Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne, and Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson. In each of these stories, inanimate toys become filled with life through the children who play with them. This also describes my childhood relationship to my stuffed animals; they took on a new meaning beyond simply being stationary textile objects.

Today, I have a similarly imaginative outlook. I am delighted by seeing little birds hop along the sidewalk, and I craft stories in my head about them. I pause to observe trees and imagine different ways in which their stories could be told. Of course, my relationship to these entities is different from my relationship to my stuffed animals, as the trees and birds are part of the world around me and do not belong to me. However, I am filled with a similar sense of creative inspiration when I spend time admiring my surroundings. This tendency towards storytelling and creativity serves as the foundation for my work in music composition. One of my main goals is to reach people through stories that are meaningful, and I hope to accomplish this goal through music and multimedia projects that not only communicate stories and concepts but also speak to people on an emotional level.

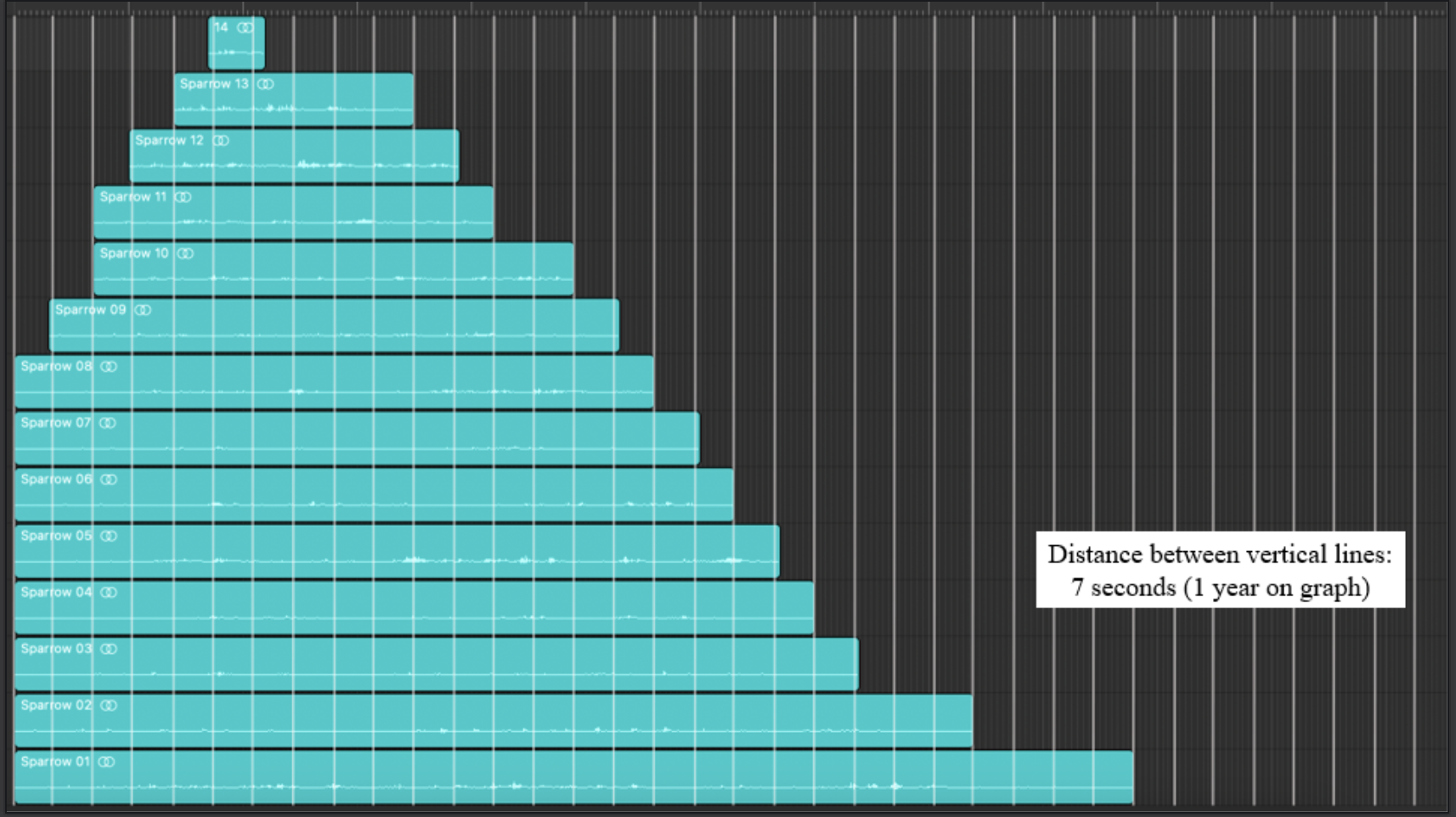

I have always seen music as a wonderful tool for communicating something, whether it be ideas, stories, or emotions. In my PhD work, I have begun to more deeply explore music’s potential as a powerful and compelling storytelling tool. One example of this exploration is a piece I created in the fall of 2023 titled “On the Strangest Sea”, whose aim is to tell the story of the saltmarsh sparrow. This tidal marsh species is threatened by sea level rise and human development, and could go extinct before 2050. My piece depicts the projected population trajectory of the saltmarsh sparrow through a technique called sonification, which broadly entails the conveyance of information through sound. The piece maps population to musical density. The tracks are meant to mirror the shape of a graph from a scientific paper - for example, when all 14 tracks are layered, that corresponds to the peak in the projected population. When there are more sparrows, the music is denser. Then fewer and fewer tracks remain as the population decreases, and the piano music eventually dies away. The number of tracks at any given point is proportional to the population at that point on the graph (7 seconds of music elapsed = 1 year has gone by in the graph).

To create this piece, I recorded individual tracks, each comprising a different set of pitches from one overarching collection, to represent the birds. I listened to previously recorded tracks while I played, improvising with myself to mimic the unpredictability of the birds. They are quiet and shy, so much of what they do is left to the imagination, especially if you’re not a scientist observing them. A pulse, which I recorded on my electric violin, is heard every 7 seconds to denote each year that passes on the graph.

The graph on which the piece was based is from Field, Christopher R., et al. “High‐resolution tide projections reveal extinction threshold in response to sea‐level rise.” Global Change Biology 23.5 (2017): 2058-2070.” Below I have a screenshot of my Logic Pro project depicting how the different piano tracks layer on top of one another and mirror the shape of the graph.

You can listen to the piece here.

As I progress through graduate school, I intend to continue exploring this sort of storytelling through music projects. Some of my ideas include collaborating with animators, creating stop-motion short films, and combining music with photography. I have for several years enjoyed pursuing amateur photography, which allows me to engage more deeply with the world around me and gather inspiration for my creative process. When I take photos, I tend to zoom in on the small details so that I can examine them in relation to the bigger picture: the context within which they are situated.

I think that the Praxis Program will serve as an ideal environment for me to learn new modes of storytelling and become better acquainted with different audiences. I am excited to learn how to use various digital humanities tools and to learn how others use these tools in their work. In addition, I am looking forward to exploring possibilities for collaborating with scholars in other disciplines. I can’t wait to collaborate with the Praxis fellows and the staff of the Scholars’ Lab!

My stuffed animals are still treasured companions. I often reflect on the time I spent in childhood imagining worlds for them; every scrap of paper I drew on, every newspaper article I wrote, and every stuffed animal’s story holds immense meaning. All of this “pretend play” served as a crucial aspect of my development as an artist and musician, helped me to develop my creativity, and deeply influenced my approach to the work I do. I’m excited to explore new worlds of storytelling through my time in the Praxis Program!

Bun & Lambie, some recent additions to my collection!

Bun & Lambie, some recent additions to my collection!